It’s a valid and important question, and one that we in the Translation Department  hear on an almost daily basis. And often, it’s not entirely clear what this certificate is, what it means, or if you even need it!

hear on an almost daily basis. And often, it’s not entirely clear what this certificate is, what it means, or if you even need it!

It certainly doesn’t help that there seems to be no standard way in the U.S. to refer to documents that fulfill the function of “certifying” a translation, or what “certifying” a translation even means – it can vary from organization to organization and state to state (and country to country, but what a “certified translation” means in other countries is complex and will not be explored here).

“Certifying” is essentially attesting that the translation is an accurate copy of the original document, to the best of the signer’s knowledge and belief, via a statement (and signature) to that effect. Oftentimes, a sentence affirming the translator’s competency to translate the languages involved is also part of this statement. Contact information for the translator and/or agency is also commonly included. We call the document that certifies our translations a certificate of accuracy.

So how do I know if it’s something I need? What is it all about anyway?

First, let’s clear up a common misconception right off the bat: there is no certification body in the United States, national or otherwise, whose credential alone allows a translator to state that his or her translations are certified translations. This concept does exist in other countries, in particular in the form of “sworn translators”; however the ability to certify translations based on this status is often limited to the country where the translator obtained this credential (a Belgian sworn translator’s certification may not have equivalent legal status in Germany, for example).

In the U.S., the American Translators Association (ATA) does offer professional certification, but, as they explain: “[ATA] Certification offers qualified and independent evidence to both translator and client that the translator possesses professional competence in a specific language combination.”

Being “certified” is thus a professional credential, and though a certified translator may do the translation, the document is not automatically certified because they translated it; it involves an extra step they must take, whether it means to provide their own signed statement attesting to the accuracy of the document, signing and dating each page, or some other measure.

So, a “certified” translation in the U.S. is really just one that is accompanied by some kind of signed statement from the translator(s) or agency attesting to its accuracy.

A translator or agency may also have a means of notarizing this statement or the translation, which leads us to another important and oft-confusing item that should be clarified: what “notarization” actually means.

Many clients request a “notarized translation,” using it synonymously with “certified translation.” But it is not the same: a translation may be certified – that is, accompanied by a statement attesting to its accuracy – and bear a notary seal and signature, but can also be “certified” without it.

As many of you probably know, notaries are required to ask for identification from the signer, and the signer must sign the document in front of them.

This is because the notary is only attesting that the person signing the certificate or translation is who they say they are, and that this person did indeed sign the document; they are not attesting to the accuracy of anything in the certificate, statement, or translation. The actual person signing the statement (whether project manager or translator) is doing the attesting, and is legally responsible in that respect. This is why some organizations, law firms, etc., request the translator sign a certificate or statement, but do not require it to be notarized.

Our certificates of accuracy do carry a notary seal and signature, but it’s only to certify the signer’s identity and signature, not the translation or its content. That’s what the certificate itself is for!

So, do I need it?

In our experience, if the document is being used for legal or other official purposes, a certificate or statement of accuracy normally must accompany the translation. Examples include:

- If the translation will be used in legal case, or is requested by a lawyer, law firm, or court;*

- If the translation is needed for immigration authorities, or has been requested by the state or federal government;

- If the translation is requested by a university or other educational institution** as part of an application;

- If the translation is to be used in certain medical contexts, for example as part of a study.

* Some lawyers and law firms require and provide their own certificates to this effect, to be completed by the translator

**Sometimes – this tends to vary by institution

I’m still not sure about this – can I see an example?

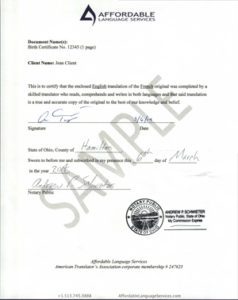

The certificates of accuracy that we issue look like this. Certificates of accuracy can take several forms, but the premise is the same: this translation is an accurate copy of the original, and I’m signing this document to affirm that.

For translations destined for other countries, including ones that do have their own methods of certifying documents and/or translators, we’ve provided this same certificate, and in our experience it has also satisfied their requirements for a “certified translation.”

We’re also able to provide certificates that cover multiple documents, and bilingual certificates (including English/Spanish, English/Russian, and English/German; others languages may be available upon request).

When in doubt – print (or email) it out!

If you’re still not certain if this certificate is something you need, or if our certificate will work for the purposes of your project, provide the sample to the person or organization requesting the “certification,” “certified translation,” or “notarized translation.” They should be able to tell you right away if it meets their requirements.

One caveat: while we’re more than happy to help you meet said requirements, one thing we can’t do is provide a certificate of accuracy for a translation that we didn’t do, or that we didn’t have reviewed by one of our linguists.

Still have questions? Don’t hesitate to contact us – we’d love to help!